The Romantic Period and The Victorian Age 1785-1901

**********************************************

"If she be small, slight-natured, miserable,

How shall men grow? but work no more alone!

Our place is much: as far as in us lies

We two will serve them both in aiding her-

Will clear away the parasitic forms

That seems to keep her up but drag her down-

Will leave her space to burgeon out of all

Within her- let her make herself her own

To give or keep, to live and learn and be

All that not harms distinctive womanhood."

(Alfred, Lord Tennyson, from

"The woman's cause is man's," Norton, Pg. 1137)

**********************************************

Austen and Browning: Comparing the Romantic and Victorian Eras

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a poet who, according to the Norton Website, "tried to find ways in poetry of giving voice to the poor and oppressed." In 1857, she created the original and enduring character of poet Aurora Leigh in her poem by the same name. Aurora is strong, sarcastic, and unshakable in her belief in her rights as a woman and artist. When we first meet Aurora Leigh, she is similar to most young women of the era; innocent, content and unaware of her own ignorance; "She lived, we'll say, / A harmless life, she called a virtuous life, / A quiet life, which was not life at all / (But that, she had not lived enough to know)" (Norton, Pg. 1093). Browning shows the reader how, as Aurora matures as a woman and artist, she sees the inherent unfairness of being female and becomes determined to succeed as an artist despite the consequences. The Norton Anthology explains that when Aurora's cousin Romney, who wishes to marry her, "discourages her poetic ambitions by telling her that women are 'weak for art' but 'strong for life and duty,' he articulates the prejudice of an age. Women poets view their vocation in the context of the constraints and expectations upon their sex" (Pg. 997). When dismissing her suitor, Aurora points out his chauvinism and her belief in the equality of the sexes; "You misconceive the question like a man, / Who sees a woman as the complement / Of his sex merely. You forget too much / That every creature, female as the male, / Stands single in responsible act and thought / As also in birth and death" (Norton, Pg. 1102). She chooses to be an artist instead of his wife, justifying herself to him with appropriate sarcasm, "You'll grant that even a woman may love art, / Seeing that to waste true love on anything / Is womanly, past question" (Norton, Pg. 1104).

"The Nightmare" Henry Fuseli, 1781

Symbolism in Romantic Period Art

In the words of researcher Petri Liukkonen, the prolific painter Henry Fuseli was "regarded as a forerunner of the Romantic art movement and a precursor of Symbolism and Surrealism." He is most famous for his painting "The Nightmare," a vivid and haunting image of a supine woman visited by demonic creatures. A professor of painting at the Royal Academy, Fuseli had many famous pupils, including John Constable, whose work is shown at the top of this webpage. Fuseli was well-respected during his lifetime and after his death. Among his many admirers were Edgar Allen Poe, H.P. Lovecraft and Salvador Dali. Dali's painting "Invisible Sleeping Woman, Horse, Lion" is said to have been inspired by "The Nightmare."

Fuseli's painting is rife with the symbolism, sexuality, and gothic horror which is associated with the Romantic Period in England. What could the symbol of the horse, peeking out from behind the woman's bed, represent? Did Fuseli purposely create a connection between the words "mare" and "nightmare" by using the symbol of the horse in this painting? Sitting atop the sleeping woman is a demonic form, perhaps a symbol of the physiological condition of sleep paralysis, referred to in the 18th century as "the night hag." According to classmate Renee Albeln; "The creature sitting on her chest is generally accepted to be an incubus - a male demon that would come to women while they were sleeping and steal their life's energy - sometimes through sexual means" (Romanticism in Pictures Discussion).

As a whole, is this painting representative of an attack on the sexuality of the woman or Fuseli himself? Liukkonen proposes that perhaps "the picture is a revenge for an unfulfilled desire, ultimately perhaps a manifestation of a jealous passion, in which the strange lover of the woman is reduced into a monster." Fuseli painted "The Nightmare" shortly after a bitter falling-out with his lover. Could this painting be the artist's revenge or a depiction of his digust with his own desires? These types of questions are classic examples of the conflicting ideas being tackled during the Romantic Period. The Norton Anthology website states that authors explored "the realm of nightmarish terror, violence, aberrant psychological states, and sexual rapacity" alongside artists of the era. Classmate Matthew Streit comments that Fuseli "portrays the woman as helpless in this painting. At the time of the Romantic literary period, woman still had very few rights and were viewed as helpless much of the time – although women like Mary Wollstonecraft were writing about the rights women should have. I would guess that Fuseli’s artwork in the present day would likely not be well received from feminists" (Romanticism in Pictures Discussion). Interestingly enough, Fuseli and Wollstonecraft were close friends, and were rumored to have been romantically involved despite Fuseli's marriage. Liukkonen reports that "Wollstonecraft, whose portrait Fuseli painted, planned a trip with him to Paris, but after Sophia's [Fuseli's wife] intervention, the Fuseli's door was closed to her forever."

Censorship in Victorian Age Art

"Because one figure was undressed

This little drawing was suppressed.

It was unkind—

But never mind—

Perhaps it was all for the best."

("In Black and White," 1894)

After his success with Salome, Beardsley became the art editor and illustrator of The Yellow Book, a popular periodical which celebrated the avante-garde artistic tastes of the 1890's, "engaging in such burning issues as sex and the role of women." (Lambirth Pg. 12). Beardsley's influence on the role of women during the Victorian Age was immense and long-lasting, as the 1890's are and were often referred to as the "Beardsley Period."

"The Yellow Book" Cover & "Lysistrata Defending the Acropolis" Aubrey Beardsley, 1894 & 1896

Literary Terms

(Phrases in quotes are taken from the Norton Anthology's index of literary terms)

Censorship: The process of editing or "restricting" the content a piece of literature before it is published. Historical reasons for censorship are "heresy, sedition, blasphemy, libel, or obscenity." Censorship of literature that contained supposedly "obscene" content was especially important during the Victorian Age.

Character: A "figure in a literary work," used to tell a story and/or a specific viewpoint. Can be a main figure used to move the plot along or a side figure used to fill out the story.

Dialogue: In literature, any conversation or vocal interaction between characters. More obliquely, also the unspoken interchange between the author and the audience. In artwork, the unspoken interchange between the artist or work of art and the viewer. From the Greek for "conversation."

Essay: An "informal" piece of writing which muses on philosophical or social issues, "usually in prose and sometimes in verse."

Occupatio: When an author claims they will not discuss a subject "while actually discussing it." From the Latin "taking possession."

Periodical: A piece of writing which is published at certain intervals, "characteristically in the form of the essay," which became popular during the Victorian Age.

Sarcasm: An ironic, often hurtful remark or statement. From the Greek "flesh tearing."

Satire: A mode of writing in which the author pokes fun at or downright "attacks" the "ills of contemporary society" as they see it.

Symbol: "Something that stands for something else," used in literature to bring to mind another thing that is inherently related to the symbol being used.

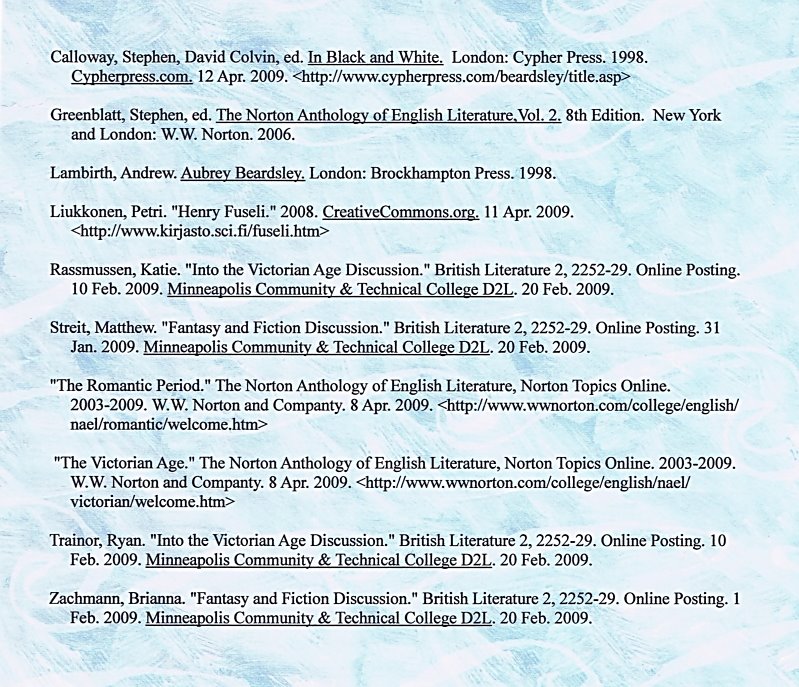

Works Cited

No comments:

Post a Comment